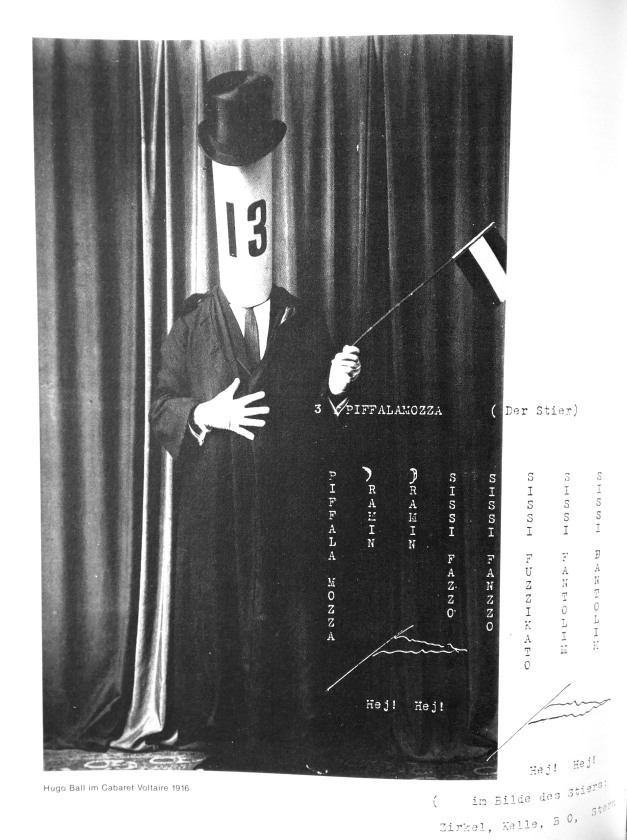

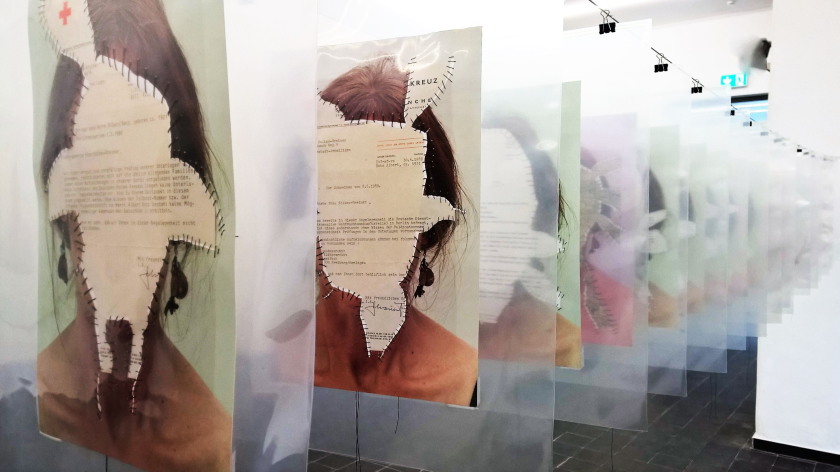

Die Suche nach dem Vater steht im Mittelpunkt der Ausstellung Teilen_Verbinden von Annegret Soltau in der Kunsthalle der Sparkassenstiftung in der Kulturbäckerei Lüneburg im Juni 2016. Eine Sequenz im Raum hängender Folien, in die Selbstportraits eingeschweißt wurden, heißt „Vatersuche“. An Stelle ihres Gesichts sind fragmentierte Schreiben von Dienststellen eingenäht, die sie um Mithilfe bat, das Schicksal des vermissten Wehrmachtsoldaten aufzuklären, von dem sie nur ein Foto besitzt.

Annegret Soltau: Vatersuche, 2003-2007, courtesy: Annegret Soltau, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016, Foto: johnicon

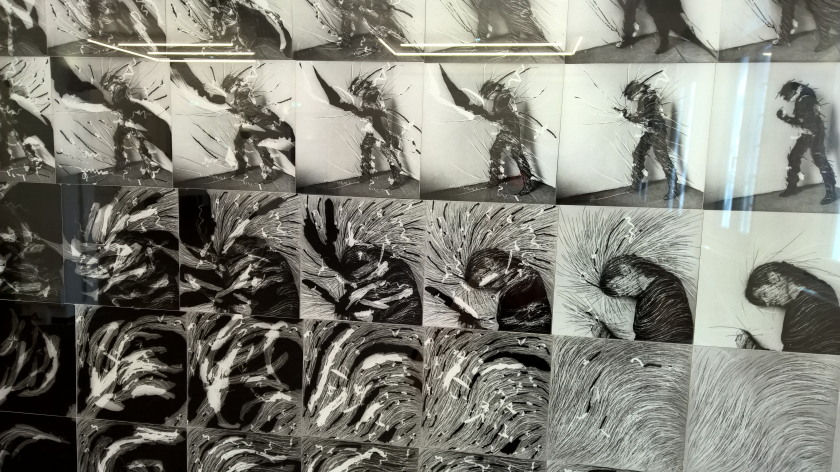

Um diese im Raum hintereinander aufgehängte Reihe dutzender Folien sind weitere Fotoarbeiten gruppiert, zu denen Foto-Vernähungen wie „Transgenerativ“ http://www.annegret-soltau.de/de/galleries/generativ-1994-2005 genauso gehören wie die zwei 150×240 cm großen Fototableaus „Hindurchgehen 1 und 2“. Sie bestehen aus je 240 Schwarz-Weiß-Abzügen von 6×6-Negativen. Jedes einzelne zeigt ihren Körper in Bewegungsphasen, die durch Ritzungen in den Negativen mit harten kontrastreichen Linien dynamisiert wurden, bis sie sich in eine futuristisch anmutende abstrakte Figur verwandelt hatten. Jedes dieser hybriden Negative aus Ritzung und Fotos wurde mehrmals in einem anderen Stadium der Bearbeitung abgezogen, bis aus jeder Fotografie ein zeichenhaftes Gebilde und am Schluss ein schwarz gefülltes Quadrat geworden war. Der Körper hatte sich so von seinem fotografischen Abbild in ein Zeichen von Bewegung und Geschwindigkeit verwandelt bis er verschwand.

Hindurchgehen II, Fototableau 1983-84, 150×240 cm (Ausschnitt), Die Bildrechte liegen bei: Annegret Soltau, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016

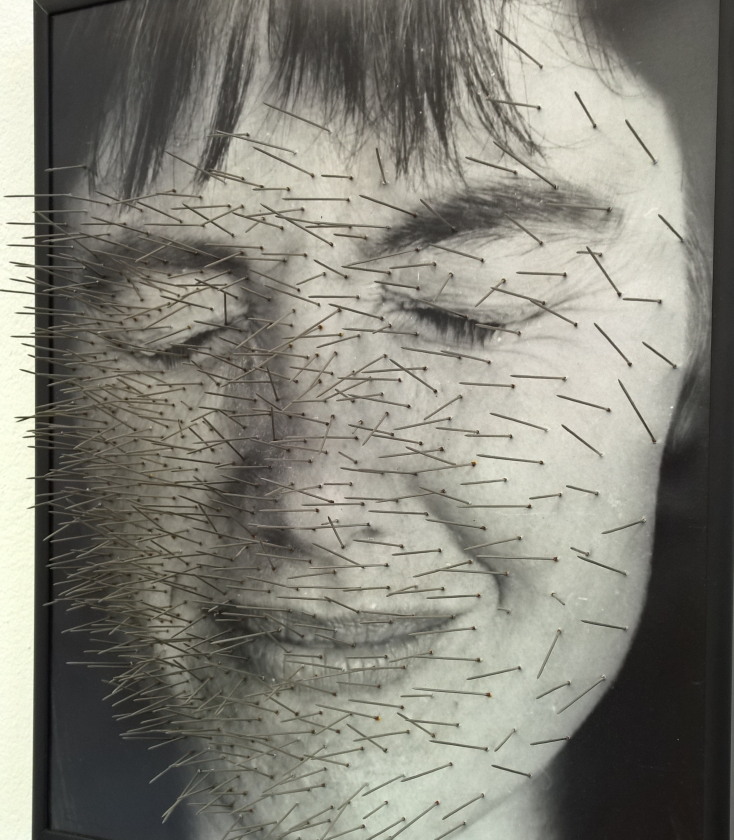

Wesentlich für die Entwicklung des fotographischen Werks von Soltau ist ihre Auseinandersetzung mit zeitlichen Prozessen, von denen die Geschwindigkeit ein Aspekt ist, den zuvor schon die Futuristen mit Krieg in Zusammenhang gebracht hatten. Mit den Fotosequenzen legt Soltau als eine der Body Art nahe stehende Künstlerin die verschiedenen zeitlichen Ebenen offen, die sich in ihren Körper eingeschrieben haben. Dabei erlauben es die bearbeiteten Negative, den Schauplatz der Einschreibung auf das fotographische Material zu verlegen und so von Leiden und Entbehrungen des Körpers zu trennen, den einigen ihrer Zeitgenossen in Performances öffentlich malträtiert haben. Die Abzüge von Selbstportraits, die jeweils mit echten Stecknadeln gespickt worden sind, bestätigen diesen symbolisch gewordenen Zusammenhang. Der Verlust des Vaters, die vergebliche Suche nach ihm und die Entbehrungen der Nachkriegszeit werden jeweils durch die Bearbeitungsprozesse des Bildmaterials als physische Erfahrung vergegenwärtigt. So durchdrangen die Nadelstiche in Versatzstücke wie zerrissene Fotos und zerschnittene Dokumente und fügten sie mit den daran hängenden Fäden wie Häute zu einem Ledermantel zusammen. Folien und Fotopapiere verhalten sich tatsächlich wie Surrogate gegenüber den traditionellen Materialien, die wie Pergament immer schon als Bildträger genutzt wurden.

Die Bildrechte liegen ich überstochen, 1991/1992, Foto, Stecknadeln (Ausschnitt), courtesy: Annegret Soltau VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2016

Auf eine archaische Art und Weise werden die insgesamt vier Generationen der Frauen der Familie zu grotesk surrealen Bildern zusammengefügt. Diese simultanen Ansichten verschiedenen Altersstufen von Frauen und Mädchen, die oft in einem Körper kombiniert sind, offenbaren Erfahrungen von Familien, die den gewaltsamen Verlust eines Mitglieds kompensieren müssen. In diesem konkreten Fall des gefallenen oder verschollenen Vaters führen die Anstrengungen einen künstlerischen Ausgleich herbei, der ein Matriarchat verkörpert, in das erst im Laufe der Zeit der Mann der Künstlerin und der Vater ihrer drei Kinder einbezogen wurde. Die Werkgruppen „generativ“ und „transgenerativ“, zwischen 1994 und 2008 entstanden, bearbeiten diesen existenziellen Zusammenhang.

Im Werk Soltaus schieben sich mehrere Zeitebenen ineinander: In den 1970er Jahren war es die Zeit und Raum komprimierende Dynamik der Bewegung, die letztlich auch ihrer zerstörerische Wirkung ausmacht. Später wird diese mit der Lebenszeit von vier Generationen verschnitten und vernäht. Und darüber liegt die Zeit, die über die Geschichte hinausweist in die Zeit der transhistorischen Erfahrung, aus der sich die „transgenerative“ Erfahrung der Zeit des Matriarchats speist.

Alle Werkgruppen und einzelne Werke sind auf der Homepage der Künstlerin: www.annegret-soltau.de einzusehen.

©Johannes Lothar Schröder, VG-Wort 2016